We round a bend on the bumpy road, and I am immediately spellbound. I want to ask the driver to stop the car so I can fall to my knees and bow in honor the beauty before me. My jaw keeps slipping towards my chest with each rock we roll over. My eyes tear up.

“My god. It’s beautiful.” I whisper over the lump in my throat. I can’t make my mouth spit out the words, “Stop, please, stop. We must see this greatness at a standstill.”

I have never before truly understood what compels climbers to summit the world’s biggest mountains, but now I catch a glimmer into their psyche. Staring at the Hindu Kush from the road snaking through Tajikistan’s southern corner, all I want to do is touch these faraway jagged, snowy peaks. Touching them with my eyes is not enough. I want to touch them with my soul.

Lluís leans over and whispers, “How are you doing?”

“It is one of the most beautiful things I have ever seen,” is all I can mutter.

I will repeat this sentence many times in the next few days as we resume our walk after a monthlong break and trek through the legendary Wakhan Valley, a place where cultures and trade have intersected for centuries.

“Thank you for bringing me here.” I smile and squeeze his hand. For many months before our trip, I would find Lluís bent over maps and atlases, looking at roads, trails and railroad tracks and stitching together a route linking Bangkok and Barcelona. And now here we are in this remote corner where the Pamir, Hindu Kush and Karakoram mountains form a knot of breathtaking grandeur. I fall into reverent silence.

There are other corners of the world that have done this me: San Francisco; a beach cove in Croatia; several places along the Mediterranean Sea; the Quilotoa Loop in Ecuador; Kuelap, Peru; Edfu and Philae, Egypt; Hede Meri, Papua New Guinea; an ashram outside Bangalore, India, and the Qadisha Valley in Lebanon, to name a few. Each place has felt both incredibly familiar and uniquely strange. They are fountains of light that fill me, that overwhelm me, that renew my sense of innocence and wonder. The Wakhan Valley has already earned a place on this “Wow” list, and I have only been here for five minutes.

(Hope this video posted. If not, I’ll reload when I have wi-fi.)

The Ride In

The journey leading to this point has been a waiting game and a test of patience.

We paused our walk in Burma and took time to soak ourselves in that country’s new year water festival. We flew to Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan to deal with the bureaucracy of securing our Central Asian visas. We haggled with drivers to get to Osh, and then had to find another driver to make the trip to Murghab, Tajikistan. We lost our cool wrangling with other drivers in Murghab who were fighting over clients, hoping to win the handful of us scattered about looking for onward travel from the cold, dusty and windswept town sitting on the edge of the Pamir plateau.

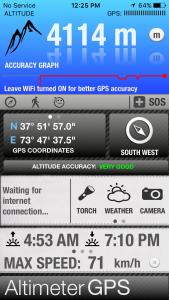

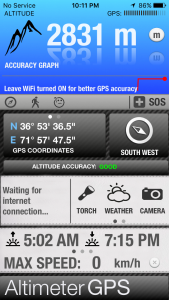

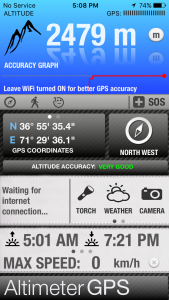

Through the good grace of the guesthouse owner, the two of us and another backpacker, found a driver willing to bypass the main Pamir highway connecting Murghab and Khorog. The driver, a nice guy if his smile says anything about him, agreed to take us directly to Langar via the rough, unpaved and sometimes dangerous road weaving through vast nothingness and reaching up to more than 4,000 meters above sea level. The ride cost us a pretty penny, but saved us at least two days of road travel, which also means picking up our walking routine two days sooner.

A couple hours into the ride, we reach a registration booth. Two soldiers push through the biting headwind and climb up from the barracks to write down our names in some record book. This will happen several other times along the valley, and luckily, despite the stories we have heard, we have no problems with bribes, shakedowns or anything disagreeable. It’s the typical red-tape that comes with filing out forms in a world that likes to contain itself within invented boundaries.

The formalities slip away, and there is only us, the mountains, the Wakhan River, and the dust the wheels kick up. Inching closer to Langar, our quiet meditation is interrupted. A family of four walking along the road needs a lift, and we squeeze them in between us and our backpacks. A couple kilometers further on, we pick up an elderly woman and find room for one more in the crowded 4WD.

I pull out my bag of cookies and pass them around. We exchange smiles and thanks yous in three languages, English, Russian and Pamiri.

I notice the sharp angular facial features of the woman next to me, her skinned browned by the sun and her lips burned by the wind. I close my eyes and breathe in the smell of the land she works and the sheep wool and leather vest she wears. As the ride’s playlist jumps between Russian pop music, Tajik songs with Arabic flair and Spanish tunes about lovers running off together under a moon lit sky, I eye the woman’s light blue backpack, mended in a few places, and wonder what she carries. I’m sure she wonders what we are hauling in our big packs, also mended in a few places and dirty with wanderlust.

We bump into each other as the car jolts side to side and loops around a countless number of bends, unlikely companions sharing a ride that will lead us in different directions.

Lacing Up Our Shoes

In Langar, finally, we can settle back into our normal. These last few weeks, while entertaining from a backpackers’ perspective, were off-route necessities and diversions from our main work of putting foot in front of another.

Loaded up on a extra calories we tacked on in Kyrgyzstan (mostly in the form of bread and dairy products we missed in Southeast Asia) and a dinner and breakfast of noodles and potatoes prepared by the lovely husband and wife teaming running the guesthouse, we set out during the early hours of the day. Sunlight is still stretching its arms over high passes, but the birds are busy flitting about celebrating spring.

It’s chilly enough to wear a cap and a Buff scarf, but not as cold as we expected it to be. We are at a lower altitude than on the plateau, and we will keep gradually descending as we move through the valley’s green gardens sheltered from the harsher weather up higher and deeper into the mountains.

We head out on the valley’s main road–its only road–and wish all our roads were like this one. Unlike Burma’s busy Asian Highway 1 with trucks speeding by and honking every couple of minutes, the Wakhan Valley road is more a trail for people and animals than a driver’s dream. It’s a mix of gravel, dirt, and sand, and sometimes there are patches of asphalt. It runs parallel to the river, wraps around farmland, passes under rows of poplar trees, climbs through barren stretches of sand dunes and rocks all shades of brown, and offers panoramic views with every twist and turn. More cows, sheep and goats use the road than cars, and it’s easy to see why the ancient silk routes curved through these parts.

“Salom,” we say to shepherds taking their animals out to graze, women sweeping around their front doors, and children heading to school. That’s hello in Tajik and Pamiri, two of the many languages spoken here. Each region has its own language, and it’s not uncommon to meet people who know three, four or even five languages. The locals are quick with smiles, and return the greeting. Frequently, they continue the conversation in Russian, their universal language and the result of being under Soviet rule until the early 1990s. I pull out a few words of the Croatian I studied many years ago, and attempt to swerve through Slavic similarities with little success.

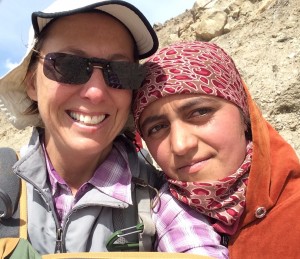

“Photo. Photo,” a young woman says, leaving her cows to pick through the grassy spots creeping out of the stone walls along the road. The world over, people love selfies and the Tajiks are no different. We pose. Her big smile turns flat and she puts on her serious face, the face many people here have when the camera comes out. I show her the photo, and she’s all smiles again.

“Spasiba,” she says in Russian, giving me a hug (the first of many hugs I will get from Tajik women) before chasing after her cows.

In the Pamir and Wakhan regions, it’s always tea time. We have been invited to have “chai” so many times, we have lost count. If we sat down with everyone who offered this hospitality, we would probably still be just outside Langar and not 200-odd kilometers away in Khorog.

But, sometimes, during some hours of the day, the invitation comes right at the moment when we need a break or long for company. We want to get to know people here, despite our inability to speak a mutually-understandable language. Communication, obviously, is not only the spoken word; there are words of the heart that speak volumes more than vocal sounds.

“Salom. Chai?” comes the invitation from Abdulo, a farmer near Darshai who is tending the field while his wife watches over their cow. Lluís and I share that look, “Sure, why not?”

We head into the white one-story house with a flat roof, take off our shoes, and walk back into time. The architecture of Pamir houses and the symbolism they represents are rooted in more than 2,500 years of history, according the pamirs.org site. The layout of the rooms, the pillars supporting the ceiling, the roof beams, and the skylight and its four-level concentric square support system come with stories that bridge Zoroastrian and Ismaili traditions and blend religion and nature in ways that look simple yet elegant.

Abdulo’s mother and one-year-old son are in the main area, and we sit on cushions on the floor near them. Rugs are the main attraction. They cover floors and walls, and guard against the cold. The room is sparsely decorated, with only a couple pictures of male family members hanging on one of the columns.

Abdulo lays a plastic mat on the floor, and his mother hands him an elaborately decorated tea pot, something we see time and again in every house we have the pleasure of visiting. Out come the mugs, the sugar cup and the bread. This is a custom we are getting used to and hope to continue back home–tea and homemade bread, the trademark signature of Tajik kindness. Abdulo’s mother, Oshormo, adds an extra touch – she brings us a big plate of fried noodles and insist that we finish it. For our journey, to keep us strong, she says after finding out that we are walking To Khorog and then to Dushanbe, the capital city hundreds of kilometers away.

There is no way to pay for this generosity. They do not accept our money. Pamir and Wakhan people do this because it their way. We can’t help but think of how the world would be a much better place if more people adopted this way.

“Kolok visior. Thank you very much,” we say with sincerity, touching our hands to our hearts, modeling the gesture people use here when they greet us and welcome us into their homes, and into their lives.

Plowing Ahead

We head back out on the road, burdened by the weight of our backpacks. I have a couple extra kilos in mine, a mistake I made when I walked into a gigantic Thai supermarket on an empty stomach and left with more than necessary oatmeal packs, granola bars and powdered soy milk. I sometimes forget that people eat wherever we go, and most days we are walking through places where I can stock up on basic supplies of one variety or another. We deliberately route ourselves on roads with villages so we access food and water in frequent intervals.

A month without walking long distances and without weight takes its toll. We are back to square one on the fitness level, forcing our bodies to respond to where our stubborn heads want to go.

My shoulders scream at me with discontent, but the pain is not like the pain I experienced in Burma. They yell at me because they are tired, not because they are being damaged. Luckily, it’s a whole body effort to keep moving forward, and my hips and legs take on much of the responsibility of getting me through the 25-30 kilometers we cover on an average day.

Then, there’s the problem of acclimating to altitude. We started walking at about 2,800 meters (more than 9,000 feet), and my throbbing headache, accelerated heart rate and mild dizziness during the first couple of days remind me to keep drinking water and take longer rest breaks. I am comforted by the fact that my stomach seems to be doing well, all things considered. Filtered water, green tea and a carb-heavy diet seem to be working for me (thankfully, because stomach issues during this stretch of the walk means more time squatting over a stinky hole in an outhouse, something I’m not inclined to do.)

Altitude changes as we crossed from the Pamir plateau and walked through the Wakhan Valley

Lluís, too, is having his share of issues we have to work through. For him, a tiny band of muscle along his right shin makes him wince. We massage it with Tiger Balm, run it under ice cold streams of water and stretch it. An unplanned rest day at the hot springs in Avj, where the mountain mineral water is said to cure eye and digestive ailments, helped some as did a change of shoes, but still the spasms come and go, and it’s hard to know how hard to push or how long to rest.

We’re both disillusioned that our weak spots have (fortunately) not come in the form of serious back, knee or foot problems, but instead show up as these annoying little things in “relatively unimportant” parts of our body.

We distract ourselves with the views, the weather, the people, the trees, the goats, who sometimes walk faster than we do.

We tilt our heads up to the sky and sigh as the sun touches our cheeks. We put our hands in the Wahkan River, the border that divides relatives in Tajikistan and Afghanistan, and send light and love downstream to the villages we will soon pass. We yank out our bandanas and hope they protect our faces from the sand and rocks being hurled at us during sudden wind gusts and under the threat of a storm that never comes. We mull over our to-do list which includes mundane things like “buy toilet paper at the next convenience store” and “remember where I packed my drivers’ license in December.” We ponder global issues that show up like “Is life here better or worse after independence from the former Soviet Union?” and “What opportunities will these children have? Will they have to leave home to find work abroad like many before them or will they create something good for themselves in their hometowns?”

Kilometers go by, and our footsteps find their rhythm again. Thoughts stop racing, and we get down to the business of relishing these precious moments in this historic place. It’s hard to believe we’re here, walking among giants. We are humbled by our smallness.

“Who would’ve thought that when we met in a square in Barcelona all those years ago that one day we would end up here together?” I say to Lluís, throwing my arms out and up. I’m in a constant state of surprise about where life continues to lead me.

“Not me,” he jokes.

“Thanks for coming with me,” I add, flashing a smile.

“Hmm… The other day you thanked me for bringing you here. Now you’re thanking me for coming with you.” Clever, that’s my guy. He is keen at picking up those subtle differences in word play. I take his hand. He kisses mine.

“Yes, I did, didn’t I?” I pause to rewind my memory. “I’m glad for both. Thankful that you brought me here, and thankful that you come with me to these crazy places.”

Maybe that’s what this walk is all about. Maybe that’s what life is about. To live life well, we need to keep bringing each other to new places physically, mentally, emotionally and spiritually. And, to make love work, we have to keep wanting to come along for the ride wherever it leads.

***

P.S. Tribute to the Backpacker and Cyclist Community

On a trip like this, we are heavily dependent on word-of-mouth suggestions, advice and recommendations. We collect immensely valuable information and make important choices based on first-hand knowledge we receive from locals and independent travelers and cyclists who follow routes similar to ours.

In that vein, we tip our hats to Hubert, Karoline, Zuzanna, Sara, Matt, Jeremie, Marta, Kamila, Jan, Adel, Axel, Lars, Kine, Brendan, Lauren, Andreas (the only other walker we met so far), the three Brits whose names we didn’t catch, Chloe, Alex, Ivan, Jerome, Shayl, Ronan (The Ginger Ninja), Anais, Nico, Yun, Kuson, Seth, Nathan, Angie, Meerim, Jendia, Mirzo, Umed, Husnigul, and the many others we met these months traveling through Central and Southeast Asia. Thank you for helping us get this far, for affectionately dubbing us “The Walkers” on the backpacker/cyclist circuit, and for being a guiding light during some of our tougher hours.

These folks are out in the world. They are of the world. They are part of our traveling family, and we hope our paths cross again somewhere else on the planet.

Many thanks and keep going, one step at a time.

It made me so happy to see this and to see you so obviously content and happy with such calm energy. You are so inspiring! What an amazing place. Thank you for taking me there, too.

Hi Barbara,

Thanks for the note. The Wakhan Valley transmits a calm I never expected to feel. I suppose the idea of walking under the protection of giants has something to do with it. We’re sad to leave them behind, but hope we get to see these beautiful mountains again another day.

An amazing narrative of your journey so far! Stsy strong, be Safe!

Thanks, Jackie. It’s a story that practically writes itself! What a gift to be surrounded by such beautiful mountains and people.

I felt like I was there with you as you transport me with your words to these remote, beautiful places. The chai ritual is lovely. Great post!

Thanks, Sunita! Tajikistan has surpassed all of our expectations. Amazing how a country we knew so little about a few months ago will now be a cherished memory. We don’t know when we’ll be back here again, but we hope to return one day.